What happens in Geneva, doesn't stay in Geneva

Progress toward an autonomous weapons treaty at the UN in Geneva amid the geopolitical shift toward normalising automated harm, rearmament, and an offensive approach to conflict.

First, some acronyms.

At the beginning of this month, Stop Killer Robots was in Geneva for a United Nations meeting on autonomous weapons. From 1-5 September, we were at the GGE on LAWS (Group of Governmental Experts on Lethal Autonomous Weapons), which operates under the framework of the CCW (Conventional on Certain Conventional Weapons), a treaty that governs the use of weapons that cause unnecessary suffering or have indiscriminate effects on civilians (it includes protocols on weapons like incendiary weapons, blinding laser weapons among others). This current GGE is mandated to operate between 2023 and 2026 to “consider and formulate, by consensus, elements of a legally binding instrument or other possible measures to address the challenges posed by LAWS”.

Now, let’s get down to what happened.

At the GGE, states continued their discussion of the rolling text developed by the Chair of the meeting Dutch Ambassador Robert in den Bosch in 2024. This rolling text contains the elements of what a potential instrument on autonomous weapons, what we refer to as killer robots, could contain. Basically, this rolling text is what states would use as the basis of negotiations of new international law on autonomous weapons — the thing we’ve been advocating for since our campaign was founded in 2012.

Since 2024, when the document was introduced as a way to guide GGE discussions, states have been debating what should be included in this document: what characterises an autonomous weapon; how autonomous weapons comply with International Humanitarian Law (Rules of War); prohibitions; regulations; and a framework of accountability. Progress continued on developing these elements of the rolling text, with new agreements made on what language to remove, amend and include.

It’s important to note here, that discussions on autonomous weapons have been taking place at the United Nations in Geneva since 2013…and in that time states have still been unable to move from talk to action i.e. negotiating a treaty that could provide real legal safeguards and a framework of accountability for the use and development of these weapons.

Further, this also normalises the idea that when war happens, and people inevitably die, there won’t necessarily be a person pulling the trigger.

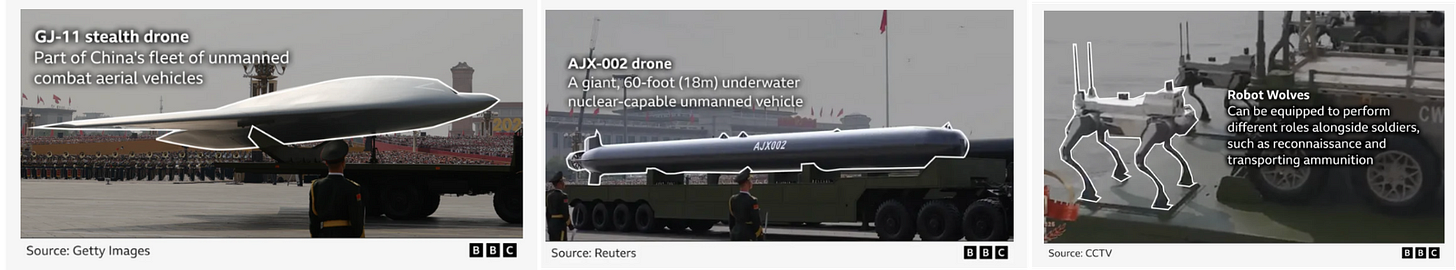

As discussions on regulation move forward slowly, innovation and appetite for increased military lethality in the world intensifies. While discussions were taking place in Geneva, China held its Victory Day Parade, in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The September 3 event was attended by dozens of Heads of State including Russia’s Vladimir Putin, North Korea’s Kim Jong Un. The Parade showcased the country’s military arsenal, including a swathe of AI-powered weapons that can operate on land sea and air.

These included Robot Wolves, four legged robots reportedly “capable of frontline reconnaissance, delivering supplies and even launching precision strikes against targets, according to Chinese state media.” The AJX002, an unmanned 18 m (60ft) underwater nuclear-capable vehicle. Additionally, a fleet of GJ-11 stealth drones was also wheeled out. These unmanned aerial combat vehicles are capable of flying alongside a manned fighter jet. This demonstration of military might falls in line with current global trends toward rearmament, but also the normalisation of AI and automated decision-making in the way war is waged. Further, this also normalises the idea that when war happens, and people inevitably die, there won’t necessarily be a person pulling the trigger.

A day after the Victory Day parade, the U.S. government announced its decision to rename the Department of Defense (DoD) to the Department of War through the 200th Executive Order since assuming office. While changing the name of the DoD back to what it was over 70 years ago, might seem superficial, it represents a reorientation toward an offensive approach to conflict. The last time the “Department of War” was used was used officially was just after World War II, the conclusion of which saw a heightened national morale and a sense of victory. In making this name change, the Trump administration seeks to return to this affective period. In discussing the change, Pete Hegseth, the Secretary of Defense Secretary (now, Secretary of War), stated that American armed forces in the Department of War would:

“fight to win, not to lose. We're going to go on offense, not just on defense, maximum lethality, not tepid legality, violent effect, not politically correct. We're going to raise up warriors, not just defenders. So this War Department…just like America, is back.”

Along with these frightening orientations toward the future, there are existing examples of automated harm and their devastating humanitarian consequences. Reports of weapons with varying autonomous capabilities being developed and used, as well as the military use of AI decision support systems in current conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine, among others.

Particularly egregious, is Israel’s use of the Lavender system an AI powered decision support system, which draws on Israel’s vast data on Palestinians in the Gaza strip to assign them a rating based on a range of behavioural characteristics. If their rating exceeds a threshold number, they get put on a “kill lists”. This is a prime example of digital dehumanisation which has contributed to immense harm and underscores the urgent need for courageous political action to prohibit and regulate the use of military AI automation and autonomous weapons. Further, autonomous weapons and militarised tech won’t be limited to the battlefield either — there is a well-worn path of military technologies being introduced and used by police and border control too.

It is clear that these diplomatic talks in Geneva are not happening in a vacuum.

It is clear that these diplomatic talks in Geneva are not happening in a vacuum. Fortunately, the GGE meeting in Geneva concluded with an acknowledgement of the urgency needed to address the situation. In the afternoon of September 5, the final day of the week-long meeting, Brazil delivered a joint statement on behalf of 42 states declaring their readiness “to move ahead towards negotiations” on an instrument on autonomous weapons systems on the basis of the Chair’s rolling text.

It is significant that this broad group of regionally and politically diverse states have recognised that they have the content to launch negotiations and share a willingness to move toward doing so. The GGE’s mandate will continue to stand until the CCW’s Seventh Review Conference in late 2026, where the states have the chance to take the next step by agreeing to a negotiation mandate for a legally binding instrument on autonomous weapons systems.

As the gap between innovation and regulation widens with increasing speed, states must urgently close it. Now is the time to ensure a world where human life is valued and protected against digital dehumanisation and the automation of killing. The safeguards that can be created at the UN in Geneva effect everyone beyond its gates — it’s time to act.